Who knows about food best? Well, the people who turn them into celebrations

Some names kept popping up when I was researching this story.

I wanted to begin with a list of people who are the acknowledged stars in Singapore for throwing parties, particularly the ones where food is the central component. I enlisted the help of colleagues and friends for my mission, starting with editor Anton Javier, who reviews restaurants for this magazine, columnists Stefanie Hauger, whose house parties are always memorable for the conversations and the energy, and Wendy Long, who has probably dined more times at the best restaurants here and abroad than an average food writer. I also took some advice from PR mavens Bing Blokbergen-Leow and Adeline Wong, who represent some of the local F&B bigwigs. Between them, I figured, I would be able to compile a decent list of subjects for interviews.

I must admit that I am at a disadvantage: my interest in food hovers between sociological curiosity and normal alimentation. I only go out for work and would be hard-pressed to name the top chefs and the restaurants they own or work for. The only names I recall are those of World Gourmet Summit’s Peter Knipp, St. Pierre’s Emmanuel Stroobant, il Lido’s Beppe De Vito, Rang Mahal’s Surya Jhunjhnuwala, Events by Olga’s Olga Iserlis, Indochine’s Michael Ma, and Tung Lok’s Andrew Tjoe – all of whom I have met professionally in the past. They’re still around and relevant, which says a lot about their stature and influence, but I’m unsure if they’re still associated with the aforementioned establishments.

Even the big hosts and hostesses that I knew have moved on, their extravagant all-nighters at hotel ballrooms or on mega-yachts replaced by intimate house parties hosted by the younger set. Occasionally, I reminisce about the parties that were hosted by Singapore grande dame Jennie Chua or the-then man-about-town Giorgio Ferrari, where such reminders as “Nothing fancy, just us” was shorthand for smart jacket and champagne.

The young set, meanwhile, have attended culinary master classes, supped at chef’s tables in acclaimed restaurants, and are adequately prepared to host elaborate dinners in their homes. Among the most charming and thoughtful that I can recall were the house parties given by Aun Koh and Su-Lyn Tan, Celina Lin, Peter Rose, Renato and Kathy de Guzman, Jeremy Ramsey, and the Lee brothers, whose spectacular Lunar New Year reunions gathered nearly everyone who was anyone to their family home. Add to these Hauger’s chic pizza nights and Long’s intimate soirees featuring sandwiches and petit fours flown in from Hong Kong and you have a picture of party town Singapore. Although I was never part of the ‘smart set’, I was sometimes invited or welcomed as a plus-one – more like a Nick Carraway than a Samuel Pepys.

But ‘the scene’, as we know it, is fickle, and more names are added to and subtracted from ‘the list’ with each passing season. I speak of a time when influencers did not exist, a Michelin star felt important, and a pandemic had not imposed restrictions on the number of guests – I needed an update.

The Boldfaced Names

If my oracles are to be believed, any list of ‘Hosts with the Most’ must include Dr. Kenneth Thean and Joo Heng – who can presumably cook, have a beautiful home, and an impressive wine collection. The said list must also include Adrian and Susan Peh, founders of Adsan Law, who are said to be as gracious as they are thoughtful. And although Elsa Van Der Nest is a culinary professional who caters events and conducts masterclasses, she is a hostess nonpareil whose inventiveness is matched by her actual food skills. Kitchen skills and knowledge of old family recipes help hosts get on the list, and for this I must mention Emil Teo.

Doubtless there are many others whose hosting prowess are kept away from social media but whose ways with food and people are laudable.

On top of the ‘Top Influencers’ list is Veronica Phua, a gourmet who apparently dines at the best establishments, and whose Instagram posts (32.4k followers) are veritable restaurant reviews that people take seriously. “She pays for her meals,” an oracle told me, which instantly separates her from those who get paid to do the same.

“Can you include food critics and reviewers who write for other publications,” another oracle inquired. “They will probably not want to be interviewed though.” Just the same, Jamie Ee, Wong Ah Yoke, and David Yip, professional food critics/reviewers made the ‘Top Reviewers/Critics’ list. Meanwhile, Bryan Koh, author of Milkier Pigs and Violet Gold, and Christopher Tan, author of The Way of The Kueh, made ‘Top Food Writers’ list.

Chef Rishi Naleendra of Cloudstreet, Chef Han Li Guang of Restaurant Labyrinth, and Chef Colin Buchan of 1880 were suggested as ‘Top Chefs’ alongside long-time favorite Chef Julien Royer of Odette.

I was briefly the ‘Hawker Stalker’ for a food magazine, now defunct, and I know that a ‘Top Hawkers’ list will be subject to severe knocking – everyone has a strong opinion on the matter. But the one name that was mentioned with respect and fondness was Ah Pui, the Satay Man. A long time ago, I was visiting friends in Tiong Bahru when Ah Pui passed by, and my host lowered a small wicker basket with some coins from the window. When she pulled it up, it was filled with Ah Pui’s Chinese “pork with fat” satay and a plastic bag of pineapple dipping sauce. It was a singular sensation.

If one is inclined to cook at home, the ‘Top Purveyors’ to consider are Culina and The Providore. Depending on the type of cooking one plans to do, Toh Thye San and Ah Hua kelong should be good sources of ingredients. I have to include Pasir Ris Produce Market because it’s one I know very well.

Like the ‘Top Hawker’, the ‘Top Food Street’ list elicited many questions; however, these four names emerged in the end: Amoy and Telok Ayer streets, Keong Saik Road, and Dempsey Hill. East Coast and Katong roads were also on the list, but were later declared as ‘evergreens’ as opposed to ‘happening’. The merry-go-round

Lunch With Luculus

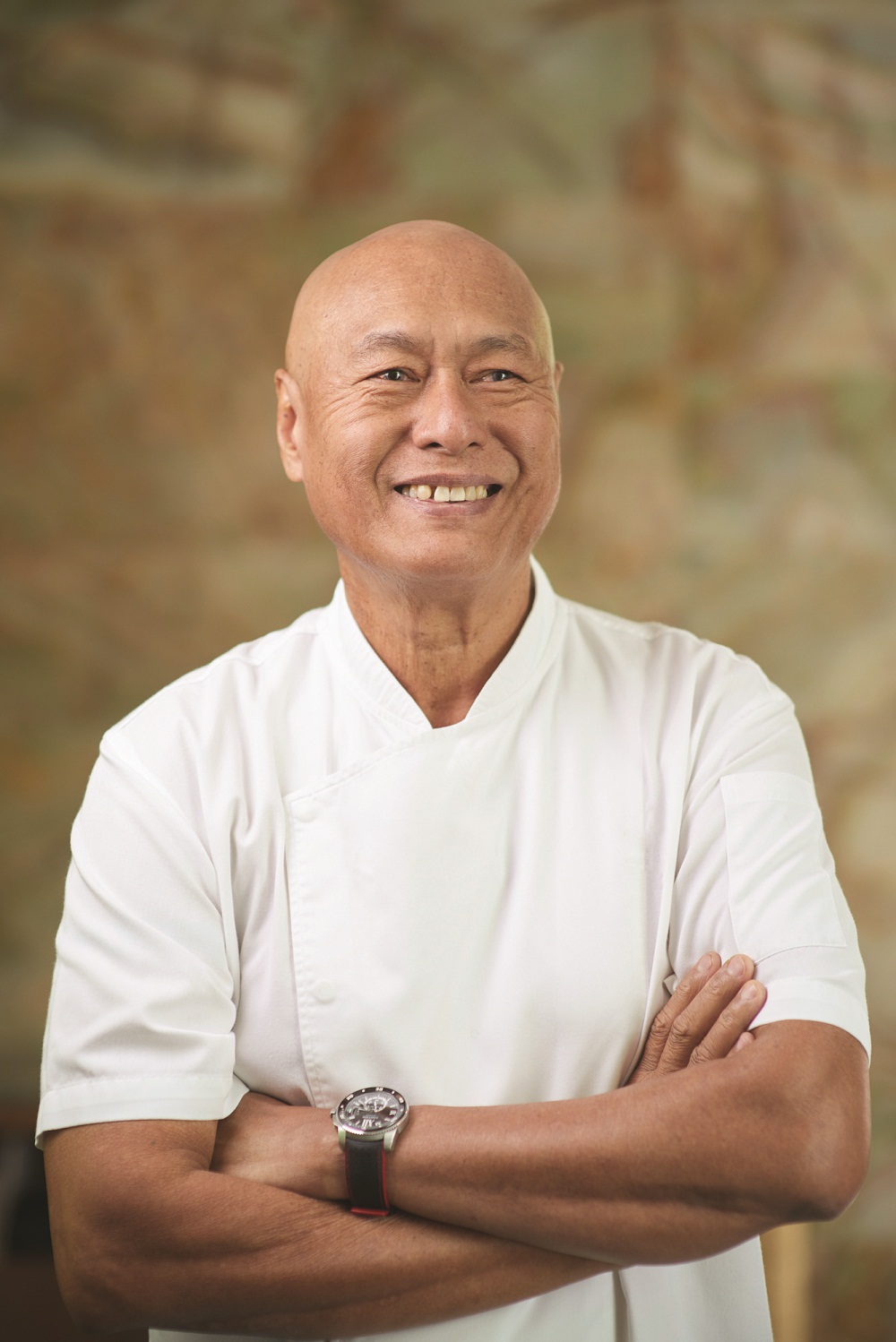

The last time Michel Lu invited me (and eight others) to lunch, I ended up unfit for work for days. We went to an award-winning Chinese restaurant at the basement of a shopping mall, each of us with a bottle or two in hand, ordered food on and off the menu, and drank like proverbial seamen on shore leave. When we were done with lunch, it was decided that we would stretch our legs and walk across the street to a wine shop for some dessert wines. That was all I could remember.

But if I still have the stamina, I would readily say yes to his invitation. Lu is a culinary giant who enjoys sharing his passion for food and good times. (That he walks several paces ahead of everyone is another story.) He has since launched his spirits brand The Orientalist, as well as The Orientalist House, a private dining establishment whose kitchen is helmed by Reiko Yoshikawa.

When I visited Lu at The Orientalist House, he was waiting for a shipment of ingredients from Japan that Yoshikawa has ordered from the suppliers’ market in Japan. This is how our conversation went.

Marc Almagro: Okay, let’s talk about The Orientalist House. You opened it last October (2020) and now you do eight pax per dinner, one seating per night, five nights out of a week.

Michel Lu: Yeah, we generally say Tuesdays to Saturdays, but some Tuesdays we block off so that Reiko gets to rest.

Almagro: Obviously, they have to book way ahead. How long is the waitlist now?

Lu: About four months.

Almagro: And when you are ready to open new dates, how do you do it?

Lu: Well, people can sign up for a mailing list on our website; I only implemented the database very recently. We had a young chef who was very different, but now the experience is really elevated – from the glassware to the lacquer trays and utensils.

Almagro: Do you specialize in a specific type of Japanese cuisine?

Lu: No. I tell people that it’s homestyle Japanese, but my friends laugh and say they don’t know what kind of home cooks like this – it is way elevated. At the moment, the finale dish is a donabe. We bring the black donabe pot along with eels from Japan. Reiko first grills them, then she steams them. She grills them a second time and it goes into the pot like a donabe. It’s fundamentally claypot rice done extremely well. Reiko has a rice husking machine, so every time the rice we serve comes from Japan and is as fresh as it can be.

Almagro: Are all your ingredients imported from Japan?

Lu: Almost all of it. Every Monday morning at, say 2 or 3, Reiko calls up her suppliers in Tokyo and she places the order for the week. Then the shipment comes either on Tuesday or, if she’s not opening on Tuesday that week, on Wednesday. But it comes in just for the dinners, which are prebooked, so we know exactly what we need.

Almagro: Payments are made in advance…

Lu: Yes, so there are no surprises. We ask for dietary restrictions, although, frankly, the menu is almost meatless at the moment. It’s focused on seafood and vegetables especially for Spring.

The vegetables are just incredible. And the fruits, ever the flowers – you don’t get them here. We had a dinner recently and Reiko served some six-year-old scallops which were so different – really meaty with intense flavors.

When I had them, I realised that having a bit of a bite is a good thing. Seeing as I eat – I sometimes like steaks from old – 12- or 15-yearold – cows from Spain. In the US, the cows (for steaks) are 30 or 36 months maximum. But in Spain, they let some of these cows grow to 15 or 18 years. Imagine the commitment, the amount of money that they spend on feed and care over the years. These are clearly free-range, heritage breed. Rubia Gallega – I think that’s the type of steak. The flavor is intense; it’s ridiculous! The first time I cooked it, I put it into the oven to reverse sear on low temperature. When I opened up the door to check, and the smell literally punched me in the face. I joked about it but it’s not really a joke. It was like stinky socks or blue cheese – that kind of funk.

But the taste was incredible. It was chewier, not like wagyu which is super soft. So, again, I think we need to appreciate everything for different reasons. Having texture and more intense flavor is one way of enjoying a certain type of food.

Young scallops, the traditional ones from supermarkets, are soft and sweet – that’s a different appreciation. I learned to appreciate the range of food that we have; it’s certainly interesting.

Almagro: Is your menu created around The Orientalist spirits? What’s the relationship between the menu and the drinks that you serve?

Lu: I am quite open about this. I don’t need to overcomplicate things. Do what you do and do it well. We don’t need to kind of weave (The Orientalist spirits) in. Previously, we used whiskey to age foie gras – foie gras torchon. We infuse it with my whiskey and we produced a certain flavor. Another time we had churros con chocolate on our western menu, and the chocolate had my whiskey in it. But for Japanese food, I think there’s less chance to do this. Gin or vodka aren’t traditionally part of their cuisine or their culture.

I know that Reiko has done gin with the finishing desert, jelly with some gin in it, and that worked out really well. But as I said, if it doesn’t make sense, don’t do it.

Almagro: What are the dinners like?

Lu: Dinner’s at seven; the guests start arriving at six of 6:30. Some have a nice, refreshing gin and tonic or a whiskey highball, others who are more adventurous would as to taste the spirits themselves.

That’s pre-dinner. When they move into dinner, majority might have some wine or some sake. We’re bringing in a lot of our own sake – all with interesting stories. We have one that is made in Miyagi prefecture that was most affected by the tsunami. During that period, the people in Hokkaido came to Miyagi prefecture to help. As a sign of gratitude, every year the brewery in Miyagi makes a special batch using Hokkaido rice.

Almagro: Isn’t that Bacchus on the label?

Lu: Yes, presumably, but instead of grapes, he has rice stalks in his hair. Only three shops in Hokkaido carry this, so for sure, this is not available in Singapore. Luckily, Reiko has her own connections, so….

Almagro: How much is dinner on average?

Lu: We only have two prices – S$170 or S$250 per person. Some people ask me what’s the difference between the $170 menu and the $250 menu. I say, “Unfortunately, I can’t tell you what it is. It’s very easy for us to say, I have wagyu and uni so the price goes up, but that’s so boring, you know? That’s not the point of what we want to do.

Almagro: Yeah, because it’s almost like you’re retailing.

Lu: Yeah, right? Everyone can get the uni or the wagyu – what’s the big deal? But what’s different is that if you commit to a S$250 menu, we will know what to serve.

Like, on Thursday, we have eight pax at $250 per head. When Reiko talks to the suppliers on Monday, she will ask for something interesting and she might end up with one of only two available

WHO EATS WHERE

Karen Cheng, Restaurateur, Gyu Bar

Bistro étroit, an unassuming one-man show that serves up perfectly executed French-Japanese dishes – just like in Japan.

Nuria Gibert, Restaurateur, Restaurant Gaig

There are small outlets at Sunshine Plaza and Chinatown Point called Victor’s Kitchen; they are a Cantonese restaurant. Their dumplings, pig trotters with vinegar, and char siew buns are super nice. It is not fancy but for us they are comfort food.

Archan Chan, Executive Chef, LeVel33

A hawker stall at Pasir Panjang. Every meal has consistently been delicious, my favorite large razor clams are usually available and very fresh.

Tea and Memories

Raised in a Cantonese-Shanghainese household in Indonesia, David Yip grew up knowing only one type of food: the refined dishes that he was fed as a boy. His grandmothers from both sides of the family loved good food, and made sure that only the best was ever served at the family table. One of Yip’s favorite boyhood stories was about eating at his friend’s house and discovering for the first time that there were foods – and standards – other than those in his house. The revelation made him curious, encouraging him to spend more time in the family kitchen where he would learn the rudiments of proper home cooking.

The Yip household kitchen was known for producing elaborate meals. If a dish called for, say, oyster sauce, it would be made from scratch. If desserts needed sugar, fruit juices would be reduced to syrup and used as sweeteners. Young David rarely ate outside and did not know how condiments in bottles tasted. There was always the family chef and the two amahs who sorted out things in the kitchen. Until he left for boarding schools, first in London and then in New York, he only knew elevated home cooking.

Yip invited me for tea at York Hotel’s White Rose Café. It was empty when I arrived. I was led to a table next to a window – Yip’s regular spot, I was told – where I found him examining some meat pies and curry puffs while surveying the traffic outside. With the introductions out of the way, we started the interview. Here’s is a snippet.

Marc Almagro: David, I enjoy your childhood stories, especially the ones where you discovered the joys of cooking in your own home.

David Yip: I grew up in the ‘60s. Back then we had a home cook who had worked as a chef for a very long time. I learned some hardcore Cantonese cooking techniques from him. I enjoyed hanging out with him in our kitchen – I’m an only child, see – but that didn’t excuse me from helping out with the chores. (My father didn’t allow me to order the maids around until I was 18 and I’m grateful for that. I learned about independence very early.) So, I would pluck tau geh and do simple tasks. When I was older, I decided to learn more about cooking so I started looking around and helping out in the kitchen of my maternal grandmother’s restaurant in London. I always gravitated towards food.

Almagro: You took many deep detours in your career – finishing a law degree, working as a clerk because you loved typing, then becoming a fashion buyer for Daimaru, a fashion journalist for a credit card magazine, a magazine publisher, and finally a book publisher with Marshall Cavendish – before you actually returned to food.

Yip: Yes. My first F&B outlet was in SOHO in Hong Kong. I rented a place where I cooked simple things like soups and sandwiches and cakes. It was a very small place – a 12-seater – but it did fairly well. From there, I built up the courage to open up a 50-seat restaurant with a bar and everything. That was when I established myself as a chef.

Back then people asked me why Hong Kong instead of Singapore. You see, if I opened an F&B establishment here at that time, I could count on support from a lot of people. Honestly, I knew all the journalists and had all the connections. But I didn’t like that. In Hong Kong, I was a nobody, and it was tougher for an F&B business to survive there. But I knew that if I could make it there, the rest would be easy.

I worked there for six years until I started to feel burned out. I was lying in bed one night and asked myself what the **** did I get myself into? I was supposed to be semiretired by then, having fun with a little café, and yet I allowed myself to get sucked into the whole thing again. So, I decided that was it. I closed down the business overnight and moved to China. I found a job consulting for a major project in Hangzhou – the Xixi Wetland – and I did that for over a year. By then my partner’s mother was growing old and we both decided to return to Singapore.

That was 10 years ago. I started freelancing again for the English and Chinese newspapers, writing abou food and travel. I also work as a researcher for CCTV (Central China Television). My academic background helps me a lot in that job.

Besides those, I’m a consultant for the Shangri-La group and for Kai Suites, Singapore’s first luxury confinement hotel.

Almagro: When you asked me to meet you here, you mentioned this is where you get your Hainanese food fix. What is it about the cuisine that you like?

Yip: Back in the ‘60s and the ‘70s, the only places where I could find Hainanese decent food were the cafés, like Shashlik and other places like that. I enjoyed going there to have my set lunch or dinner. My palette can be very Asian but after living in London and New York, I also got used to continental cuisine. I like good pies but, honestly, it’s difficult to find them now in Singapore.

Almagro: Why is that?

Yip: Back in the day, a lot of the hotel chefs were Hainanese. They earned very good money. A lot of them also owned kopitiams. They were very skilled in cooking Western-style steaks, so I associate western food with the Hainanese. I love how they mix the East and West. You know, they loved the British but they also brought in their own elements. I love that very unique flavour which I couldn’t get it in London or in New York.

But things have changed so much in most hotel kitchens now that you hardly can find one Hainanese. They’re almost extinct! (Laughs.) Even here, now, there’s only one Hainanese left.

Almagro: Why do you think that’s the case?

Yip: I think it’s because people are getting richer. In the past, the Hainanese had fewer options. Back then all the races were very territorial when it came to certain fields of expertise. The Hainanese dominated the hotel kitchen. Later on you had the Teochew and the Hokkien. Back in the day, if you weren’t Hainanese, you couldn’t step into the kitchen. Now, I can’t even find one Hainanese chef at Raffles Hotel. (Laughs.)

Now that we have more hotels we don’t have enough Hainanese chefs. We are seeing more Western chefs in the kitchens, they are employing the Cantonese, the Hokkiens, and a lot of Malaysians as well.

Almagro: What do the Hainanese bring to the kitchen?

Yip: The East-West. Look at these pies. The Hainanese make their own puff pastries, which is now very rare. A lot of people buy…

Almagro: …puff pastry in a box.

Yip: Puff pastry is very tedious to do. I don’t know about now, I haven’t asked. The last time I went inside the kitchen, two years ago, they were still making puff pastries. They knew how to make the roux, which Cantonese, in the past, couldn’t. The Hainanese were the experts in making sauces; they actually picked it up from Western kitchens.

A few years back, they took mee siam off the menu. I called the manager. The next time I came, itnwas back. (Laughs.) I can be that persistent.

Almagro: Well done, well done.

Yip: I mean, I hate to say it, but we might be the last generation that could eat traditional food. Food should evolve – I agree. Whatever we eat now actually reflects current taste – there’s nothing wrong with that. But I guess I’m just being sentimental by insisting on having that old stuff. It’s common to hear the old folks lamenting that the food today is not as good as what they had. Typical right? The food has evolved and I believe in that. That’s one of the reasons why I enjoy working with young chefs.

Almagro: But you draw the line on inferior ingredients or….

Yip: …or poor techniques. I always remind the young chefs who train under me that they can create, innovate, whatever, but they must have a foundation. It’s only when you understand the foundation then you can know how to create. I can accept new flavors, new styles, new trends. I mean, I was in fashion, but I cannot accept it when someone incorporates wrong techniques into

WHO EATS WHERE

Damian D’Silva, Chef, Restaurant Kin

My secret dining place used to be a secret but it’s not anymoreI I’ve always felt that if there was one hawker dish that deserved recognition, it has to be char kway teow. My not so secret haunt is located at 335 Smith Street, #02-32 (S) 050335.

Gabriele Rizzardi, Wine Director, Buona Terra

My kitchen at home where I usually cook and enjoy a simple pasta for supper after work, made with three key ingredients - good quality pasta, butter, and ton of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese from Parma.

Heman Tan, Chef-Owner, MOONBOW

I visit my good friend Justin Quek’s restaurant Chinoiserie four to six times a year. The xiao long bao with creamy carrot puree and Boston lobster bisque are my favorites.

Prepare to be Amazed

When culinary consultant and caterer Elsa van der Nest presented her version of the Lunar New Year lo hei salad, she had even the most jaded socialites talking for days. The 100 per cent organic starter featured herbs and flowers doused with a sweet pomegranate molasses dressing. She served it in an antique blue and white bowl the size of a basin, and handed her guests – already warmed up with champagne and canapes – a pair of silver chopsticks for tossing the salad.

For another Lunar New Year dinner, van der Nest served goose with little oranges on a bed of noodles tossed with French and Russian mushrooms, and spread out on an antique silver platter. Traditional, yes, but with a dollop of uplifting extravagance.

Of course, one must get invited to one of van der Nest’s parties to experience the full ‘Elsa Effect’, as some members of the party set put it. Those who don’t, however, can enlist in the Elsa van der Nest masterclass, conducted in her home, which initiates a budding hostess – or host – into the art of giving parties. Failing that, one could still visit van der Nest’s Instagram account where masterclass schedules are announced and images from her latest events are posted.

She invited me to her amazing house one afternoon, and as we settled down for tea, brought me backstage at the exclusive events she has masterminded, walking me through the tricks of the trade, the backbreaking work, and, of course, the triumphs. Here are the highlights.

Marc Almagro: Elsa, will you take me back to the day you first came to Singapore?

Elsa van der Nest: Well, I sold my restaurants and my cookery school in South Africa to move to Singapore. I met my former husband, in an art gallery at Prince’s Building in Hong Kong. But as I was returning to Cape Town two days later, we decided to meet for lunch, dinner, lunch, dinner. I flew back home to my school and I got a call from Johan on a Tuesday morning. He said, “What are you doing for the weekend?” I said, “I’m going to see my foodie friends, and we’re going to stay at a friend’s boutique hotel. He said, “Come to Hong Kong for the weekend instead.” I just got back on a Sunday, opened my school on a Monday, and flew back to Hong Kong on a Thursday. I stayed there until Sunday and flew back Monday.

Almagro: See what love can do?

Van der Nest: I’m very adventurous. It’s not about love, it’s about the adventure. (Laughs.)

And then we traveled backwards and forwards backwards. Johan was with an English law firm in Hong Kong (he’s a qualified barrister in the UK). I moved here in November 2002. Then I was headhunted to be the culinary director of Raffles Hotel’s cookery school. A cookery school director, and then SARS arrived.

Then at the age of 40, I fell pregnant with twins. They all told me I had to stop work, and I did. Six months after the twins were born, David Yip from Marshall Cavendish approached me. You must know David? He said, “Can you please do an Italian and French book for us?” So, there I was, six months after my children’s birth, writing two books at the same time. We did all the photography in my house – with two six-month-old babies around.

After four years, I couldn’t stand being at home. My children had grown; I felt that it was time to move on. In South Africa, I had two restaurants. I did all the cakes. I did the catering for all the top events. I had a cookery school where I trained young people to go into the industry. It was full on.

Almagro: What a major change. You must miss being part of the action.

Van der Nest: I did. Some of the students that have come through my school are now the top restaurant professionals in South Africa. They did six months at the academy with me, and then six months in the industry.

We did the state dinner for Nelson Mandela when Bill Clinton came; it was on a wine farm and we worked out of a refrigerator truck. I did the catering for golfer Ernie Els and all those sports people from around the world. We did it on the Rupert & Rothschild wine farm, starting with a picnic on the lawn followed by a fivecourse dinner. My kitchen was in the wine cellar among the wine barrels. At two o’clock in the morning, we did a barbecue.

Can you imagine it? From a big magnificent picnic out on the lawn, to a spectacular five-course wedding dinner, and a barbecue at two o’clock in the morning? I couldn’t walk three days after that.

Marc: I can imagine. Yeah, that’s tough. So, Singapore is easy compared to what you have done.

Van der Nest: Yes, to a degree. But we’ve done some challenging things here as well. We did the food for a very interesting event for Audemars Piguet at the old railway station. For four days. We had no running water there, so we had to prepare all the food at the Armenian Church and ship it down to the venue. We also did an event at the rooftop of Liat Towers. Before the guests arrived, the heavens opened and it poured. I had no roof, no cover over my food. Thank God it stopped, but we had no water and I had no light.

We did the catering for Crazy Rich Asians (location shoots) with Diego (Chiarini) and Stephane (Colleoni) of OSO Ristorante. (They were my partners in my catering business.) I ran the cold kitchen and worked in the Japanese kitchen on my own, while they did the hot food. We had to do breakfast so I would go to the baker on Killiney Road at midnight and pack breakfast. We would be sitting on the pavement on Killiney Road at four o’clock in the morning, discussing the next morning’s breakfast. Then I would go to OSO, open up the place at 4.30 in the morning, work again until 11 o’clock at night. It took us all a month to recover after that. It was three weeks of solid filming.

The night of the wrap party up on the roof at Fullerton was the first time in my life that I wore slipslops to a party. We couldn’t wear shoes; we couldn’t put anything on our feet. They were sore.

Almagro: And it hasn’t slowed you down one bit, because you’re still…,

Van der Nest: No. We just keep going. Last week, I had three classes – Monday, Wednesday, Friday – here from 10 in the morning to about three. So—

Almagro: Now, give me a bit about the course. What does it comprise?

Van der Nest: I do two to three masterclasses a week. If you take a look at what I put up every month on my Instagram, I do Mediterranean, Moroccan, French, and Italian – that’s where you get the theme. I have done Cooking with French Birds for the French masterclass, and A Touch of Spice for the Middle Eastern.

I take seven participants at a time. It’s a culinary lifestyle masterclass. They come here and we spend three hours in the kitchen. But before they come, I decorate the table in the morning and then we do all the food. We make it beautiful, decorated, and put it all on the table.

Then they sit down for lunch with a SoulSister’s gin and tonic, and then they leave at about 2.30 or 3 o’clock. That has set a very interesting turn in Singapore because ladies who were never interested in food, but came to be entertained, now come all the time because they love it. And when they go home, they are in their kitchens.

WHO EATS WHERE

Emmanuel Stroobant, Chef-Owner, Saint Pierre, Shoukouwa & Kingdom of Belgians

As a vegetarian, Israeli food is on the top of my list. We never miss Ottolenghi when we are in London, and now we have Miznon in Singapore.

Caroline Tan, Co-Founder, Beats, Bites & Cocktails, and F&B consulting company Ladies & Gentlemen

My grandma’s kitchen. My relatives and I love her delicious and heart-warming Cantonese soups that are cooked over charcoal for half a day.

Chef Maksim Chukanov, Head Chef, Cure Singapore

I love Greek cuisine and my to-go place is Bakalaki. Chef Spiros is a very talented and hospitable guy and I always have a great time there.

Chef Oliver-Truesdale Jutras, Head Chef, Open Farm Community

I like visiting Morinaga to indulge in quality Japanese food and beers, and the chef surprises me all the time with his creativity